Back To Blog

Georgia’s Election Disaster Shows How Bad Voting in 2020 Can Be

July 23, 2020Written by: Morehouse College

This op-ed was originally published on July 22 in The Conversation.

______

As the nation mourns civil rights icon John Lewis, a congressman and lifelong advocate of voting rights, the mayhem in his home state’s most recent election serves as another egregious example of how a citizen’s most sacred act in a democracy – voting – was undermined and even denied after a federal law protecting voters’ rights was abandoned by a 2013 Supreme Court ruling.

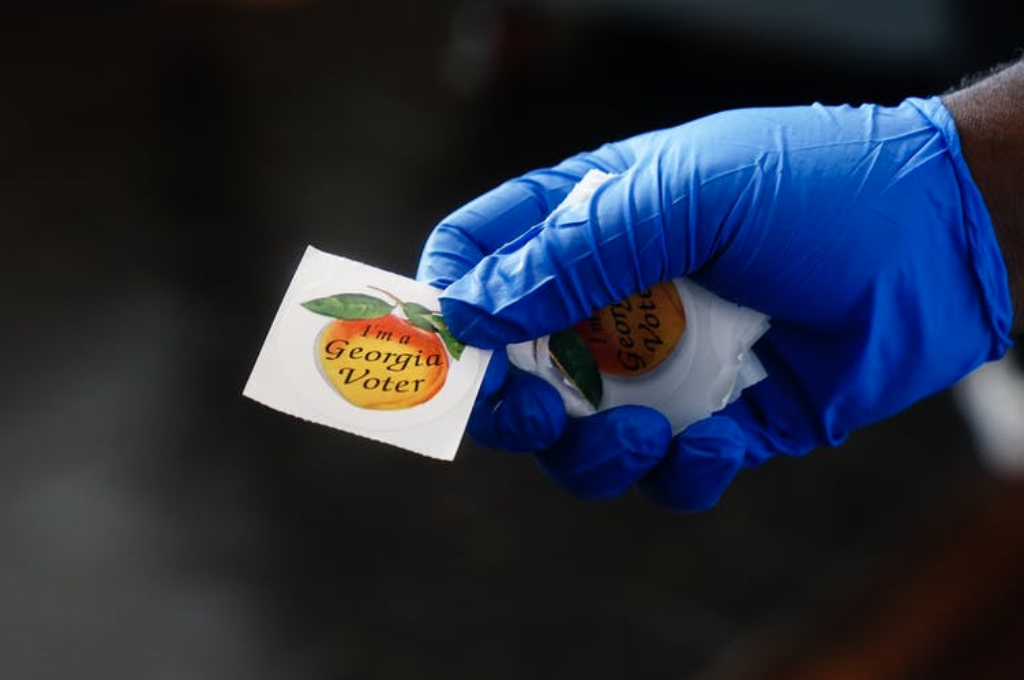

Georgia’s presidential primary election on June 9 was a nightmare mix of inefficiency and discrimination that shows how difficult it is for many Americans – particularly Black Americans – to participate in their democracy.

Hundreds of voters, many in majority Black areas, waited four, five and even seven hours to cast their ballots. Some even faced down police seeking to send them home without having voted.

I am a scholar who studies voting rights and voter suppression. When I spoke to longtime Georgia voters throughout the day, each one of them remarked that they “had never seen an election like this in the state of Georgia.”

The state’s primary was an example of what should not happen in a democratic country. It is an experience that has implications beyond Georgia, and that carries warnings for problems with the November presidential election and the legitimacy of the results.

Not enough places, ballots or help

Georgia’s primary election was postponed twice from its original March 24 date, because of fears of spreading the coronavirus pandemic through in-person voting.

A million and a half Georgians applied to get absentee ballots that would have let them vote by mail. But an unknown number of them never received their ballots and were forced to vote in person to ensure that their votes would be counted. Ultimately only 943,000 ballots were cast by mail.

Georgians didn’t always know where to go to vote: 10% of polling places – including 80 in the state’s most populous county alone – were closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The state-run website that let voters look up where they should vote was down for several hours in the morning and worked only intermittently throughout the day. When the site was up and running, some voters still could not find their correct polling locations and visited precincts where poll workers told them they couldn’t vote.

Experienced poll workers were ill or feared getting sick, so the state had to recruit, train and dispatch new ones right before the election. Many poll workers were insufficiently trained and uninformed, especially about when voters were entitled to absentee, emergency and provisional ballots.

There weren’t enough polling places, either. Several sites that normally serve 2,000 to 3,000 voters had to accommodate as many as 10,000 because of the consolidation.

Some polling places, especially in majority Black areas, had major delays because new voting machines weren’t working correctly. Many polling places across the state opened two and three hours late. The new systems, including printers, scanners and tablets, had trouble throughout the day, causing additional delays.

Precincts ran out of provisional ballots and envelopes and printer paper. County governments, the NAACP and other civil-rights groups appealed to county courts to get orders extending polling hours beyond the usual 7 p.m. to make up for the delays. One precinct didn’t close until 10:10 p.m.

As if that weren’t enough, it rained on voters in long lines with no shelter.

A pattern of vote suppression

Early in the day, Brad Raffensperger, Georgia’s Republican secretary of state, blamed the mayhem on the counties, which administer the election, for not properly preparing for the state’s new electronic voting system. County officials responded that the state was the problem.

The state’s Republican leadership did nothing to prevent this democratic disaster from happening, even though it had happened before, just two years ago.

In the 2018 election, Republican Brian Kemp, then Georgia’s secretary of state, was running for governor. As the state’s chief election officer, since 2017 he prepared for the election by using a variety of voter-suppression tactics that could influence the results.

In 2017 Kemp purged more than half a million voters from the rolls under the state’s rule that voters who have not voted in two or more previous elections could be required to re-register before voting again. And he applied another rule that disqualified voters whose names in election rolls did not exactly match their identification documents.

In addition, for the 2018 election, Georgia had fewer polling places open than usual, reduced the availability of early voting and required proof of citizenship before a person could register to vote.

Kemp’s efforts paid off. He won the election against Democrat Stacey Abrams by a nose in the closest governor’s race since 1966.

That narrow victory may have reinforced Georgia Republicans’ fear, shared by President Donald Trump, that if it’s easier for people to vote, the GOP will lose more elections nationwide.

The end of federal supervision

All these manipulations and changes are legal. That’s because in 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act, removing the provision that protected people’s right to vote free from discrimination.

In their 5-4 Shelby County v. Holder decision, the justices removed the federal government’s power to evaluate, preapprove or block discriminatory voting laws in states like Georgia that have long histories of voter discrimination. That means there is no more federal oversight to ensure that qualified voters can gain access to the polls, and no recourse beyond state governments for voters who fear they have been unfairly denied their rights to vote.

In Georgia and other Republican-led states, officials have used the freedom provided by the Shelby decision to take official actions that make it harder for Americans to vote, and more likely that future elections will look like Georgia’s did on June 9.

Despite all those barriers, though, Democratic voters and Black Georgians turned out in record numbers last month. Enough of them waited, and cast their ballots, to surpass the 1.06 million votes cast in the 2008 primary when Barack Obama beat Hillary Clinton.

Whatever the reason for such large numbers overcoming such significant obstacles, it is thanks to the determination of countless individual voters – and not state or county election officials – that Georgians were able to vote in meaningful numbers.

With the Voting Rights Act gutted, other states may feel freer to suppress their citizens’ voting rights the way Georgia did. Voters across the nation may face similar circumstances in their communities – but there is still time for them to demand better from their officials.

______

Adrienne Jones, J.D., Ph.D., is an assistant professor of political science and the director of the pre-law program.