Back To Blog

Honoring a Forgotten Past: An Author’s Journey

February 15, 2021Written by: Morehouse College

History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are consciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities and our aspirations.

-James Baldwin

A RARE DISCOVERY

I rarely miss an opportunity to lecture and share the fascinating backstory that prompted me to write my historical novel entitled, The Friends of Freedom: A Battle for the Heart and Soul of America (Seaside Press, 2020).[1]In essence, this book is the product of an intensely personal journey involving over thirty years of intermittent research and writing. Yet as I frequently tell my audiences, this arduous undertaking has been an absolute labor of love. In this regard, I truly believe that the story of how and why I came to write it is just as important as the novel itself. Perhaps other educators, parents and writers will agree.

My journey began in 1980 shortly after the discovery of some rare archival materials that have since been dubbed, “The William H. Dorsey Collection.” This rare collection consisted of over 380 hand-made scrapbooks, along with numerous first edition books, unpublished manuscripts, biographical sketches, old photographs and memorabilia that had been surprisingly relegated to a janitor’s closet on the campus of Cheyney University of Pennsylvania.[2] As it was explained to me, these rare archival materials had been (for some unknown reason) stored for well over fifty years in this closet located in Biddle Hall, an administration building that was at that time scheduled for a major renovation.

Accordingly, everything had to be removed from this building in order for the renovation work to proceed. As a result, maintenance men were hurriedly and indiscriminately throwing these archival materials in a large dumpster along with scores of broken desks, chairs and miscellaneous trash. In the midst of this frenetic activity, an unnamed janitor was curious enough to open some of the brittle and tattered scrapbooks. And lo and behold, they were filled with newspaper clippings from a bygone period lost in the mist of time. These clippings had been meticulously cut out of newspapers and pasted into these homemade scrapbooks. And they apparently represented the life’s work of one man, William H. Dorsey.

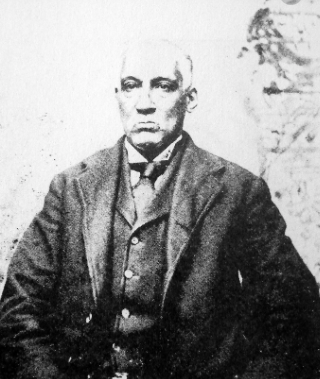

William H. Dorsey (1837-1923)

This large scrapbook collection, along with the other artifacts were his personal property that he had amassed for over four decades. Many of his scrapbook clippings pertained to noteworthy people and events that occurred between the period 1870-1902. It should be noted that most of the newspapers represented in these scrapbooks are now defunct and out of print. Thus their value as primary source materials cannot be overstated. The information and social commentary contained therein are priceless and irreplaceable. They provide us with a unique window into Dorsey’s world and offer insight into the mindsets of his contemporaries including ordinary citizens, journalists, advertisers and activists who sought to shape public opinion and react to events that were of local and national significance. Of course, Mr. Dorsey had no way of knowing that his collection would end up in a janitor’s closet for over fifty years without the temperature and humidity controls needed for the proper storage of archival materials. I suspect he would have been disappointed to know that his collection had landed in such an ignominious resting place.

UNDERSTANDING AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY THROUGH THE EYES OF THOSE WHO EXPERIENCED IT

The fortuitous discovery of these timeworn and decomposing materials clearly dishonored Dorsey’s painstaking efforts to preserve and pass down a rich historical legacy. Thus I will be forever grateful to that unnamed janitor and Dr. Herbert Womack, that discerning Cheyney administrator who rescued the Dorsey Collection in the nick of time. At his direction, the collection was removed from the trash dumpster and brought to a secure location. He subsequently selected me to catalogue, index and preserve these deteriorating materials that were to be microfilmed, stored in acid free containers and relocated to Cheyney University’s main library. This is when my journey began.

For the purposes of this discussion, it is important to note that Dorsey was not a mere hobbyist or collector of rare objects such as coins, stamps and the like. He had amassed these archival holdings not as a frivolous pastime but as a part of a far more serious and deeper obligation, namely that of historical transmission and the intergenerational fortification of cultural identity. Further research revealed that Dorsey was a part of a small and aging group of African American collectors of African Americana who had an avid interest in books, history and historical preservation.

In 1897, this Philadelphia-based group of African American collectors and bibliophiles formed an organization known as the American Negro Historical Society (ANHS) and Dorsey was chosen as their chief “custodian.” It is clear that the work of these elderly raconteurs and self-appointed chroniclers was quite intentional. They had a passionate and informed pride in their cultural lineage and wanted to preserve and transmit “Negro history” to future generations with a specific purpose in mind. Writing in 1902, Robert Adger, the president of the organization expressed their overarching and far-reaching purpose:

We want the Newspapers, the Churches and the Parents to tell their Children what our past condition was, and about those dear people who are dead and gone, of the sacrifices they made on our behalf, and the grand opportunities we are now offered.

Adger’s assertion provides a clear indication that the ANHS was primarily concerned with the education of children and the continuous cultivation of cultural identity and collective memory. The assumption being that if young people knew their people’s history, they could better understand the importance of the historical moment and take full advantage of the relative freedoms and opportunities that lay before them (even in 1902). Here we discern the critical intersection linking history with hope and ANHS’s deliberate attempts to use history as a means to foster a keen sense of agency. If the youth of their generation could understand history, they could see their strivings and accomplishments in the broader and more meaningful context of an ongoing collective struggle. The ANHS’s activities and teachings conveyed an unabashed call to duty. The accumulation of knowledge and the preservation of historical materials was primarily fixed on sustaining intergenerational identity, hope and exertion and had little to do with mere sentimentality and nostalgia.

A similar pedagogical intent was expressed by William Still, another prominent ANHS member and author of the seminal book, The Underground Railroad (1872) which was one of the rare books found in the Dorsey Collection. Still dedicated his inspirational book to “the friends of freedom, to heroic fugitives and their posterity in the United States.” Most importantly, he was a consummate participant-observer who was in a unique position to write such a factual book. He was widely known as an important and trusted operative in Philadelphia back when the city was a major hub of the Underground Railroad and the center of a nationwide abolitionist movement (approximately 1837-1865).[3]

His now celebrated book documents the sacrifices and struggles of our many ancestors who were fugitive slaves and who went to such extraordinary lengths to obtain their freedom. Their escape stories make up most of Still’s book and are largely profiles in courage, agency and ingenuity. In addition to these dramatic accounts, Still’s book pays homage to free persons of color who acquitted themselves as informed citizen-activists who were by no means silent and apathetic on-lookers. And they were certainly not passive victims or muted witnesses to the horrors and injustices of slavery and racial oppression. In retrospect, the ANHS’s combined work coincided with the concurrent uphill battle to secure basic citizenship rights for African Americans citizens in spite of the legitimization of societal and institutional racism that prevailed at that time.

Still also wanted to pay homage to his many high-minded white allies who proved themselves to be stalwart “friends of freedom.” To their great credit, they had opened up their hearts and homes in a time when scores of footsore, malnourished and penniless fugitives were desperately making their way to Philadelphia and all points north of the Mason-Dixon Line. Some of them even gave their lives in this cause. His heartfelt portraits and sketches of these persecuted and committed helpers and “station-masters” reflect the higher registers of our national character. With these men and women also in mind, he wrote:

The heroism and desperate struggle that many of our people had to endure, under the terrible oppression that they were under, should be kept green in the memory of this and coming generations.

In the aggregate, Dorsey, Still and their aging ANHS colleagues had seen and experienced a lot. Most of them lived through a relentlessly oppressive time that witnessed the entrenchment and steady proliferation of slavery, a bloody and costly Civil War (which African Americans proudly fought in) and a short-lived Reconstruction Era that ended with the legalization and common practice of institutionalized racial segregation in the North and untold Jim Crow abuses in the South that lasted well into the turn of the century. And through it all, they seemed to understood that the preservation of history was somehow important in facilitating the “greening” of collective memory in their offspring and in “coming generations.”

They wanted to pass down a deep racial pride that would serve as a bulwark against the steady onslaughts of a racist society that stubbornly sought to relegate African Americans to the lowest rungs of the socio-economic ladder and assign to them the permanent status of second-class citizens (at best). They patently rejected the precepts of white supremacy and defiantly challenged the pervasive view that in the larger scheme of world affairs, Black lives were less valuable and simply did not matter. As race-conscious men and women, they wanted to create an ideological counter-narrative fused with racial pride, an important narrative that recognized and celebrated the long history and achievements of a scorned people.

Reflecting on their motives, I have drawn the conclusion that they must have believed that history provides important, life-sustaining knowledge. Moreover, this knowledge had (and has) the potential to strengthen vital links in a lengthening chain of collective consciousness and continuous cultural transmission. They apparently believed that the cultural legacy that they tried to preserve would somehow provide edifying spiritual food for both the onward and inward journey of their immediate progeny and succeeding generations. And if somehow, unborn generations could grasp this critical nexus linking the past with the future, they might derive sustainable hope, and most importantly, develop the inner strength and resilience that had enabled them to survive and thrive during some of the darkest days in our national history. Clearly, their visionary concerns went far beyond the pedantic and spiritless transfer of information devoid of any moral meaning and significance.

Unlike many trained scholars, they did not approach history as a detached and purely academic discipline focused on causal analyses and interpretations. I believe that they were trying to convey something much more; something that would be of timeless value to help sustain and fortify future generations of African American children and posterity in general. That wanted to defiantly promote and bequeath to future generations this ideological counter-narrative that would refute the destructive myth of black inferiority and mitigate the sting of widespread social and institutional racism. As an aspiring author, I have always wanted to stand in that rich, time-honored tradition.

Today, the private collections of these little-known ANHS members have been paid scant attention. This is largely because these valuable primary source materials have been scattered far and wide, lost, hoarded or simply neglected much in the same way that the Dorsey collection was mishandled.[4] If nothing else, the “mistreatment” of the Dorsey collection has taught me that we have a profound duty to properly preserve valuable archival materials held in our custody. As an educator, I also believe that our intergenerational obligation extends beyond archival preservation. In sum, as teachers, students and parents, we would all do well to expand an awareness of many of our unsung ancestors who helped lay the foundations of the modern civil rights movement and ultimately secure and safeguard many of the rights and privileges we currently enjoy.

As I completed my indexing tasks, I remained firm in the belief that there had to be some literary mechanism that might help me effectively bring salient components of the Dorsey Collection to light. Like many, if not most academics, my first impulse was to write a book. That inchoate objective seemed to closely align with the ANHS’s very intentional goal to promote cultural awareness and facilitate the intergenerational transfer of useful knowledge. As I originally envisioned it, my book would excavate some of the Dorsey Collection’s treasures and raise them up as part of our shared cultural inheritance. And young audiences (in particular) would be the principle beneficiaries.

But in preparing for this literary task, a number of realities had to be considered and confronted head-on. Foremost among them was the problem of “existential disconnection.” Teachers often complain that for many of today’s students, history is a rather dull subject which they perceive as having no direct relevance to their lived experiences (James Baldwin’s introductory quote to the contrary). Thus there was the distinct possibility that my work might fall on deaf ears. Second, Dorsey’s interests were broad and eclectic and his diverse newspaper clippings were presented in no particular thematic or chronological order. As an untrained educator, he seemed to believe that his diverse clippings stood on their own merits. Thus he made no attempt (for the most part) to link his recorded biographical sketches and events to concurrent and contributory social and political trends. In the absence of critical analyses and social commentary, the wide-ranging content in his miscellaneous scrapbooks lacked coherence and were not presented in any meaningful social context that could make my writing task easier. I would have to establish thematic order and settle on an organizing pattern if I was to weave a compelling literary cloth out of mounds of fragmentary and disjointed materials.

Finally, there was the issue of literary style and “readability.” These earnest ANHS members were highly intelligent. However, they were apparently unschooled in literary style, form and function and had limited pedagogical training. To further the point, William Still for one, was by all indications, a well-read man. But in writing his book, he was nonetheless keenly aware of his literary shortcomings. In the preface to his book, he humbly writes:

The writer is fully conscious of his literary imperfections… Nonetheless he feels that he owes it to the cause of Freedom, and to the Fugitives and their posterity in particular, to bring the doings of the U.G.R.R before the public in the most truthful manner; not for the purpose of amusing the reader, but to show what efforts were made and what success was gained for Freedom under difficulties.

That said, both Still and Dorsey were men of high moral character who valued truthfulness. And what they may have lacked in literary training, they made up for with their factual accuracy and their unimpeachable sincerity of purpose.[5] Their efforts to preserve history are laudable and demonstrate a deep desire to fortify the remembrance of many of our forgotten heroes and heroines and rescue them from the dust bins of human history. Through the years, I held to my commitment to bring this rich history to life in a way that acknowledged the aforementioned existential disconnection and other realities that might diminish my ability to connect with students and contemporary reading audiences. Then, in a memorable revelatory and introspective moment, it occurred to me that this goal might be best accomplished by drawing upon the time-honored efficacy of historical fiction and tapping into the power of story that was skillfully embodied in “enabling texts.”

THE IMPORTANCE OF ENABLING TEXTS

Somewhere between the second and third iterations of my novel, I had the good fortune of encountering the work of Alfred W. Tatum, a noted reading specialist whose scholarship focused on the critical need for “enabling texts” in the school curriculum. And all of a sudden, I received a spark of inspiration that was at once, liberating and directive. Tatum described enabling texts as texts that are “connected to larger academic, cultural, economic, political, social and personal aims and help young people define who they are and what they can become.” Such texts strengthen the conscious motivation of students to engage positively with others for their own benefit and that of the larger society.[6] Tatum offered this observation

We need to (re)connect African American adolescent males with texts in order to begin shaping a positive life trajectory for them. Unless powerful texts anchor literacy reform-texts that are models of rich language-these young men will continue to be underserved in schools. They must be enabled and engaged by texts mediated by educators who use these texts to broker positive relationships and improve their lives.[7]

Reading Tatum’s books reminded me in a profound way that good literature has the power to transform lives. And with this purposeful and ambitious goal in mind, I re-wrote The Friends of Freedom with the hope that it could ultimately be received by my target audiences as a bona fide, richly-textured enabling text, one that was contemporarily relevant and was unabashedly written so as to catalyze critical introspection and a deep contemplation of our shared history. Tatum’s advocacy further convinced me that teachers are obligated to assign, interpret and mediate books that are personally meaningful and culturally relevant in order to empower students to be active lifelong learners.In this same vein, I re-wrote and re-styled my novel as a “gateway text” that might stimulate their curiosity and encourage them to engage in further research on the subject matter.[8] Moving beyond “existential disconnection,” I also wanted to acquaint and re-connect students with their history in ways that underscored the deep reverence for life and learning that characterized many of their heroic ancestors who resiliently persevered in an oppressive and openly hostile society that in many ways mirrors contemporary realities.

In this regard, I am pleased that more and more high school and college teachers are assigning my novel as required or supplemental reading for their courses in Civics, American History and African American Studies.[9] Others are using the novel in their Freshman Year Experience and Leadership Studies Programs. Now in its third printing, The Friends of Freedom is still growing in popularity. High school and college students seem to appreciate its strong storytelling aspects and its fictionalized dramatization of actual events. I am always humbled and pleased to receive favorable reviews and comments by colleagues and classroom teachers. Their encouraging words have helped to sustain my writing and lecturing throughout this long journey. In particular, I shall always remember the testimony of a high school teacher whose words filled me with a deep sense of satisfaction. She wrote:

My students cannot put the novel down. It is the most amazing sight! You can literally hear a pin drop when they come in and open their books. Fellow teachers have told me that they constantly hear the students discussing the book in the hallways, the lunchroom, and their classrooms. They are not just reading a story. They are learning about extremely important events in our nation’s history.

HARNESSING THE POWER OF STORY: OCTAVIUS CATTO AND THE GENERATION OF CRISIS

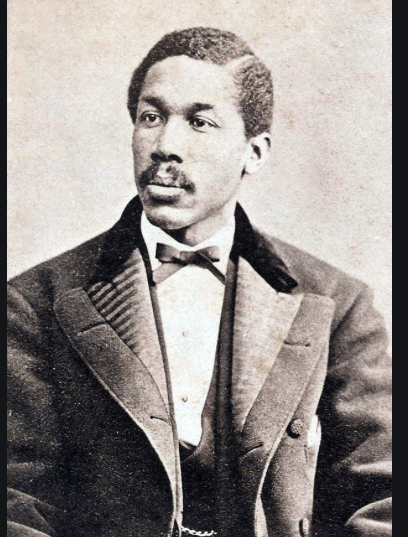

My exposure to Tatum’s work marked the beginning of my efforts to re-boot my novel. The emergent challenge before me was that of establishing a focus for the new book that I had in mind. First, it was important to delimit and distill a wide range of rich primary source materials into a compelling and coherent story that serious readers and young people alike might find of interest. That contemplative task subsequently led me the selection of one the novel’s principal characters, Octavius Valentine Catto.[10] In so many ways, he was the quintessential hero, a beloved figure who was deeply respected by his contemporaries.

Octavius Valentine Catto (1839-1871)

I first “discovered” him in 1981 when I read one of Dorsey’s scrapbooks that focused on the proceedings of the “the trial of Frank Kelly.” Kelly was an Irishman of ill-repute who was tried but wrongly acquitted in the murder of Catto in daylight and in plain sight of countless eyewitnesses (Microfilm Roll #2, Scrapbooks 76-77). With further research, I learned that Catto had come of age and rose to prominence during a time that coincided with what the noted historian Lerone Bennett Jr. has aptly described as “the generation of crisis.”

During this period, the volatile and irrepressible debate over slavery intensified and ultimately led to the outbreak of the Civil War. At the conclusion of the war, Philadelphia and the nation as a whole had to heal deep ideological and sectional wounds. In addition, the city had to adjust to the sweeping transformations of industrialization and urbanization and the steady influx of European immigrants in pursuit of the American dream. Philadelphia like so many other urban centers became a thriving social “melting pot” and experienced the stresses and strains of assimilating and educating a culturally and racially diverse citizenry.

Clearly, Catto’s life was inextricably interwoven with the day to day struggles and social conflicts that confronted this beleaguered generation of crisis. Thus I consciously moved away from a strict biographical approach towards a wider and deeper examination of the zeitgeist of this historical period. In this way, I could illuminate the hopes and aspirations of the local African American community that sustained Catto’s social activism. This was key to the subsequent flow and cohesiveness of my storytelling. Most importantly, this shift allowed me to creatively tap into the phenomenological realities of my historical characters as I subtly invited my readers to imagine what those characters might be thinking and feeling as they watched pivotal trends and events in American history unfold. And in relatively short order, my emerging book took on a certain relevance, readability and momentum.

This conscious decision to tell a simple story and introduce Catto to today’s audiences allowed me to flatly reject the idea of writing for the benefit of a small circle of scholars, academicians and “history buffs.” And as long as I stayed close to the words, actions and aspirations of my primary sources, I knew that I could not go wrong or veer away from the intergenerational emphases of our ANHS ancestors who fervently believed that historical preservation and storytelling were integral parts of their (and our) obligation to succeeding generations.

Through the years, I have come to accept the fact that well-told stories can uniquely elevate and sharpen our moral sensitivities. Stories are also enduring and powerful instruments that can unite people who have a shared history and common values. Thus The Friends of Freedom was reconstituted so as to convey interrelated stories that allowed readers to see their educational pursuits and social activism in the historical continuum of our ongoing struggle for social justice. In a very real sense, Catto’s story, set in 19th century Philadelphia, is our story, our shared national story. In the final analysis, this ongoing intergenerational story can inform our future prospects for demonstrating responsible citizenship and leadership in a democratic and increasingly multi-cultural society. Drawing on the efficacy of historical fiction, I used my literary imagination to imbue Catto and most of my principal characters with the same faults, foibles and imperfections that bedevil us all, particularly during this era of “racial reckoning” that we are currently experiencing.

In my fictional (but fact-based) account, the inquisitive and maturing Catto and his contemporaries are placed in difficult circumstances and they move in a society that is in chaos and turmoil. Life is unfair, laws and punishments are unevenly applied and their daily existence is riddled with constant danger and hostility. But through it all, they strive to understand and meet their obligations and heed the dictates of simple justice. Their natural instincts to survive merge in interesting ways with their desires to lead meaningful and purposeful lives. They are uniformly men and women of great courage, compassion and dauntless agency.

Many of these ancestors gave time, some gave money and some gave their lives in our collective advancement towards a “more perfect union.” For that reason alone, they are certainly due our homage, but not as romanticized heroes and heroines to be placed on psychological or marble pedestals. Lest we forget, if there was true greatness in them in was because there was goodness in them. That is why they are useful subjects for historical analysis and moral reflection. That is why they are worthy of remembrance and that is why their stories need to be told. Those stories keep us “awake” and ever mindful of our civic duty.

I completed The Friends of Freedom even more convinced that a keen historical perspective and elevated social consciousness are inextricably linked and mutually reinforcing. Together they provide regenerative correctives to the widespread apathy, alienation, hopelessness and intolerance that infects and permeates our society. More particularly, history provides a fascinating vantage point from which we can observe the slow, grinding evolution of our American form of democracy and understand the social forces (then and now) that impede its progress, distort its meaning and restrict its great humanitarian promise. By understanding and clearly identifying those forces, students can become more informed citizens who can participate in the forging of a new national narrative (if there be the desire to do so). Through enduring enabling texts and guided reflection, we can fuel their quest for an even greater America and help them envision better realities that they may want to boldly will into existence.

Observe the forward march of human history and you will find full-scale victimization and unspeakable cruelties and injustices. However, you will also find ample intergenerational sustenance to propel our forward momentum towards becoming a just nation dedicated to the tireless pursuit of liberty and justice for all. Examine American history and you will witness great tragedy. But look beyond the African American vale of tears, and you will most assuredly appreciate the strength, intelligence, resilience and courage of a triumphant people.

For example, the horrific ravages of the American slave trade are an ugly and pernicious sight to behold in the bright light of historical examination. But look beyond the shadows and you will find many whites of various religious and ethnic persuasions who openly challenged and vehemently protested against that atrocious practice at every turn. And you will surely discover the depth of their humanity and appreciate their full-throated and unflinching commitment to spiritual values and the highest American ideals.

I hope The Friends of Freedom will continue to be received as a hopeful and healing enabling text that heightens the educational and social aspirations of young people of all ethnic backgrounds and religious beliefs. In some small way, maybe it will succeed in expanding an all-important sense of moral duty. Or perhaps it will prod them to critically examine their own lives and better appreciate the freedoms they currently have and strive to extend those same freedoms and protections to others. Who can say? We sometimes underestimate and forget the value of positive role models (living and deceased) and the powerful testament of lives well lived. Like Mr. Dorsey, Mr. Still and their ANHS colleagues, I believe that this is far more than wishful thinking.

POSTSCRIPT

Tragically, Octavius Catto’s life was cut short (at the age of thirty-two) by an assassin’s bullet. And in truth, those who were responsible for his murder were never brought to justice. Herein lies a story within a story and the critical intersection between the history that Dorsey and Still tried to preserve and the escalating violence and social discord that continues to threaten our democracy and diminish our hopes for racial justice in the 21st century. For over a century, Catto’s was a forgotten hero and his legacy languished in relative obscurity. But all of that is gradually changing. Today, Octavius V. Catto is fittingly implanted in our collective memory of the faithful and the fallen. His name has been entered in the scrolls of the honored dead who “gave the last full measure of devotion” to the cause of freedom and the actualization of our cherished democracy. And that is certainly as it should be.

In recent years, a diverse group of conscientious citizens created the Octavius Catto Memorial Fund with the goal of erecting a statue named in his honor, to be placed at Philadelphia’s City Hall. And after a lengthy period of advocacy and fund raising, that vision was finally brought to fruition. The long-awaited statue was formally dedicated and unveiled on September 25, 2017 by Mayor James Francis Kenney, a thoughtful civic leader of Irish extraction who had been a staunch supporter of this initiative through the years. On that occasion and others, Kenney would repeatedly say, “My hope is that some day, every child in Philadelphia — and America will know as much about Octavius V. Catto as they do about George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.”

[1] This book was originally released in 2009 as The Rains: Voices for American Liberty. It has since been rewritten, retitled and re-released under the current title.

[2] Chartered in 1837 as the Institute for Colored Youth, Cheyney is widely regarded as the nation’s oldest historically black college or university.

[3] I am dating this high period of the Underground Railroad from the establishment of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in 1837 to the passage of the 13th Amendment of the Constitution in 1865.

[4] A notable exception to this generalization is the Leon Gardiner collection that is currently housed in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

[5] In his 1970 celebratory preface to The Underground Railroad, the distinguished historian Benjamin Quarles aptly described Still’s style as “clear, if plodding.” He further noted that “Still’s organization is haphazard, following no discernable pattern other than a faint chronological line.”

[6] In contrast, Tatum describes a “disabling text” as one that reinforces a student’s perception of being a struggling reader incapable of handling cognitively challenging materials. The common use of such texts in the classroom contributes to student frustration and related academic under-performance.

[7] See Alfred W. Tatum’s Reading for Their Life: Rebuilding the Textual Lineages of African American Adolescent Males, Heineman Press, 2009.

[8] To encourage further research, my work of historical fiction provides an actual timeline of historical events and offers provocative footnotes. It also designates in bold type the actual (verbatim) spoken or written words of organizations and historical personages as reflected in their personal writings, publications, speeches and correspondences.

[10] Sometime during my period of intermittent writing, a well-researched, non-fictional account of Catto’s life and times was rendered. SeeBiddle, Daniel R. and Dubin, Murray, Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America. Philadelphia: TempleUniversity Press, 2010.

______

Sulayman Clark is currently a guest lecturer and has previously served as Vice President for Institutional Advancement and Senior Development Officer at Morehouse College.

Other posts you might be interested in

View All Posts

November 22, 2021 |

Morehouse Faculty