Back To Blog

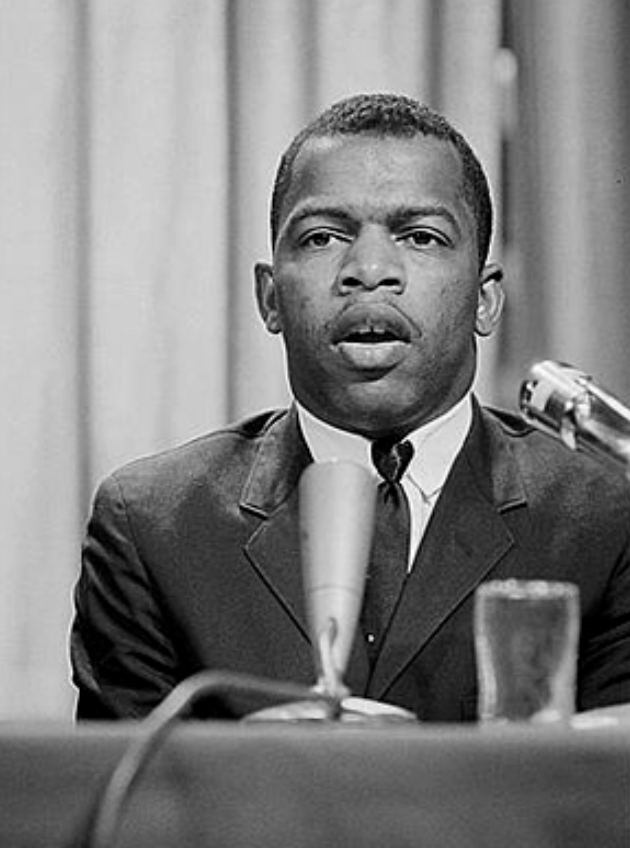

Passing the Torch of Freedom: W.E.B. Du Bois, John Lewis, and C.T. Vivian

July 18, 2020Written by: Morehouse College

W. E. B. DuBois died on August 27, 1963, on the eve of the March on Washington. It sent waves of grief across the Atlantic, with protestors in Accra, Ghana, and Washington, DC, honoring the contributions of the fallen giant. Du Bois along with Morehouse President John Hope and other progressive black leaders organized the Niagara Movement to advance civil rights and promote liberal arts education for black youth in response to the rise of Jim Crow laws and Booker T. Washington’s push for vocational education and accommodation to the segregated social order. Du Bois helped found the NAACP and edited its Crisis magazine. Through his political activism in the NAACP and in the Pan-African movement, he would be a public voice for black freedom in America and worldwide. And while he departed the United States to live his final years in Ghana before the rise of the student movement of the 1960s, he had prescribed it over a decade before it emerged in full force. As Sterling Stuckey writes in Slave Culture, DuBois addressed a group in 1946 in Columbia, South Carolina, and proclaimed to the youths: “You have got to make the people of the United States and of the world know what is going on in the South. You have got to make it impossible for any human being to live in the South and not realize the barbarities that prevail here.” Stuckey called this a “prophecy,” which was fulfilled by a later generation of student activists.

It was poetic for DuBois to die on the eve of the biggest single civil rights demonstration in United States history up to that point. And it also seems poetic that in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement, what has been called the biggest protest movement in American history, two veterans of the 1960s student movement-- C. T. Vivian and John Lewis—would die on the same day. Working at the grassroots level with local organizers, building inter-racial political coalitions of peace and justice, and pressing the federal government to enact major civil rights legislation, they carried the torch that DuBois and others passed to them from previous generations of struggle. In fact, on the day after DuBois’s death, John Lewis gave a fiery speech at the March on Washington that gave voice to the discontent of student activists with the status quo.

The three had distinct paths and organizational affiliations—DuBois split with the NAACP, embraced Marxist analysis, increasingly extended his political reach outside the United States, and died in political exile in Ghana. Much of C. T. Vivian’s grassroots organizing during the high tide of the Civil Rights movement played out in the context of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference founded by Martin Luther King, Jr. and later through nonprofit organizations to bring about social justice. In contrast, John Lewis worked as a grassroots organizer in and chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and later launched a career in Congress, where he continued to advocate for peace and for the most vulnerable.

And while they took different routes at different times, they also circulated through the same black Southern spaces. DuBois worked in the countryside of Tennessee and graduated from Fisk in Nashville, where several generations later both C. T. Vivian and John Lewis pursued their degrees before joining the Nashville student sit-in movement in 1960. They had trained in nonviolent direct action with James Lawson and joined forces with other students such as Diane Nash to desegregate lunch counters in downtown Nashville. And they also circulated through Atlanta, with DuBois spending two stints at Atlanta University, first at the turn of the twentieth century and later during the Great Depression. Rev. Vivian and Congressman Lewis took the last, long legs of their journeys in Atlanta. Exposed to the region by birth or migration, the culture, beauty, and struggles of black Southerners undergirded them in their work.

With lives and deaths that were interwoven in many ways, they changed the social fabric for the better, but their work remains unfinished. Some of the problems they confronted have been intractable, even in a vibrant city like Atlanta. The city is a capital of inequality with low rates of upward mobility for its poorest citizens. And across the country, people joined mass protests sparked by anti-black violence. Though he couldn’t be with them in person, John Lewis met with youth activists in a virtual town hall in June to encourage them in their movement.

Fighting until his final days, Lewis like Du Bois died at a high time of political protest. But their work and the work of C. T. Vivian have enduring value. By reflecting on their words, actions, commitments, and sacrifices, they can help spring us into right action and offer us guidance, inspiration, and encouragement in what will most likely be a long struggle ahead.

______

Frederick Knight is associate professor of history at Morehouse College, where he is also director of the Institute for Research, Civic Engagement, and Policy at the Andrew Young Center for Global Leadership. Dr. Knight has published a number of book chapters and articles on black history, and he is the author of Working the Diaspora: The Impact of African Labor on the Anglo-American World, 1650-1850.

Tag(s):

Morehouse Faculty