Back To Blog

Prison Education Initiative at Morehouse

February 18, 2021Written by: Morehouse College

The Andrew Young Center for Global Leadership (AYCGL) at Morehouse College strives to serve as a hub for promoting social justice in various forms, including the delivery of a humanities education for incarcerated and returning citizens in Georgia. We are also actively engaged, together with our local and national partners, in advocating for criminal justice reform and supporting those working on behalf of men and women in the carceral system. Compared to the number of incarcerated people in other states, Georgia has an extremely large prison population of > 60,000 men and women, plus thousands more who are on probation or parole.

Several faculty members from Morehouse began teaching classes with incarcerated students or returning citizens several years ago, often in partnership with Common Good Atlanta (CGA). The Clemente-model of prison education at CGA, which emphasizes the humanities, was modeled in various ways on the BARD Prison Initiative. This semester, Spring 2021, we are pleased to announce that five faculty members from across academic divisions at Morehouse – including four AYCGL prison education teaching affiliates – will teach, or are presently teaching, classes on critical thinking and creative writing (Dunn, CTEMS), the history of Black entrepreneurship (Hollingsworth, Business), literature (Claiborne, English), Philosophies of Freedom (Jensen, Philosophy and Leadership Studies), and the US Constitution (Winfield Murray, Esq., Political Science). The AYCGL faculty affiliates teach at either Burruss Correction Facility, which is south of Morehouse, or the METRO Re-entry Program in downtown Atlanta. These higher education courses for incarcerated students and returning citizens extends the reach of Morehouse beyond the borders of our physical campus.

A number of Morehouse College faculty are actively involved in other aspects of higher education in prisons: Dr. Adrienne Jones recently taught a prison education class on ‘National Government,’ remotely, in Minnesota, with colleagues from Howard University and the University of Minnesota; Adrienne is also a topic expert for the JAMII Sisterhood. Dr. Sinead Younge taught a J-mester course on the intersections of race, gender, class and the prison industrial complex. Sinead volunteers with Common Good Atlanta and delivers guest lectures at several carceral institutions in Georgia; she also conducts assessments of prison education programs and serves as an advisory board member for the Georgia Coalition for Higher Education in Prisons (GCHAP). Winfield Murray, Esq., and Dr. Fred Knight (Institute for Research, Civic Engagement, and Policy) are working with Gideon’s Promise, whose mission is to transform the criminal justice system by building a movement of public defenders who provide equal justice for marginalized communities, and other organizations across Atlanta to address social injustice in the criminal system. The AYCGL will host the Gideon’s Promise 2021 Training Program for young public defenders this summer. Taken together, these Morehouse-AYCGL initiatives constitute a multifaceted approach to providing higher education to men and women who are incarcerated and returning into the community.

For the purposes of this blog entry, I want to focus on three of our colleagues, two of whom are AYCGL teaching affiliates and the other an AYCGL social justice fellow: viz., Dr. Claiborne, Dr. Dunn, and Dr. Jones. I asked our colleagues what led them to their work in prison education and criminal justice reform as well as why this work is so important and what we ought to keep in mind, both as individuals and as an institution, when extending what we do at Morehouse beyond our physical borders and into carceral spaces. Like many of us, Dr. Claiborne and Dr. Jones were inspired by the PBS documentary, College Behind Bars, which follows the journey of several incarcerated students of debate in the BARD program. Dr. Claiborne says that she wanted to take her role as an educator as well as someone who’s committed to social justice more seriously. Dr. Stephane Dunn says: “I’ve had had very closely related family members incarcerated, but I’m also deeply concerned about the structural injustices within the prison industrial complex system, particularly the ongoing history of racism and sexism.” Dunn says that she appreciates the work of scholar-activists like Angela Davis, e.g., Are Prisons Obsolete? (2003), and others who have been addressing this problem for a very long time.

When asked why prison education is important, Dr. Claiborne points out that in doing this work we are fulfilling the mission of Morehouse College and that by engaging in prison education we are also working at countering economic disparities. This work is important because it is part of a greater calling. She’s also reminded of what Bryan Stevenson says: “The opposite of poverty is not wealth; the opposite of poverty is justice.” Dr. Jones says that this work important because all people should have access to education, and especially if they are incarcerated. Jones seeks to create an internal environment of hope and gain some traction for creating options once a person is de-carcerated and returns to the community. Dr. Dunn believes that education is that doorway to a greater transformative sense of self, life, and work for everyone. Teaching about the empowerment that language and the knowledge it affords us is really important. Dr. Dunn says that while we're trying to open the door to education for incarcerated men and women, our own perspective is bound to open wider and in unexpected ways too. Dr. Jones believes that this work is critical because there are very few instructors of color in prisons. This is statistically true, said Jones, and it was also clear to her from the feedback from her students: it mattered that she was Black, most certainly, since most prison educators are white, but it also mattered that the curriculum was delivered in a way that was engaging as well non-judgmental and free of religious proselytizing. We should approach our incarcerated students just like we do our conventional students, advises Jones, so that the fact that they are incarcerated is not felt to be a liability.

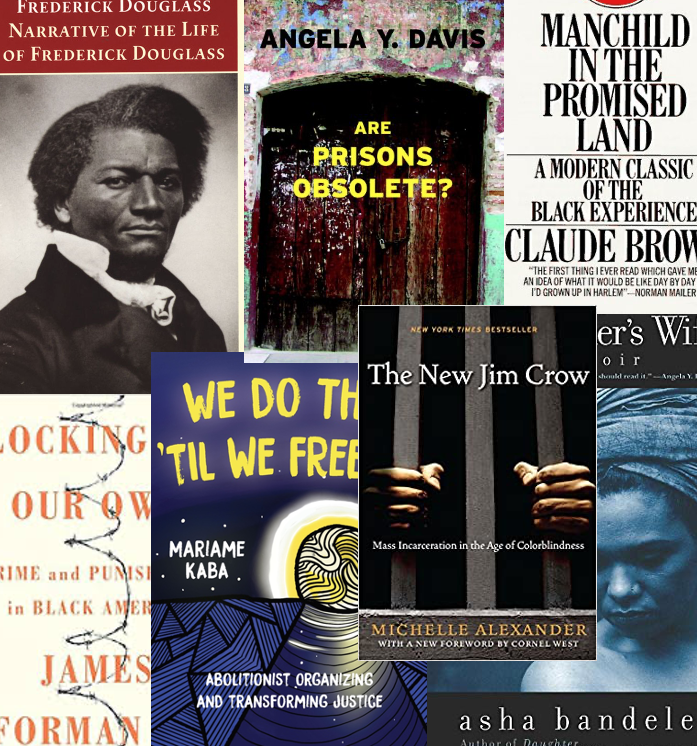

When asked what books or other resources they’d recommend, our faculty recommended the following: the works of Angela Davis and James Baldwin, the autobiographies of Malcolm X and others, including Frederick Douglass’ Narrative and Claude Brown’s Manchild in the Promised Land, Mariame Kaba’s We Do this ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice, Nathan McCall's Make Me Wanna Holler, Anne Moody's Coming of Age in Mississippi, Amiri Baraka's poetry, also his play, The Toilet, Michelle Alexander's book on the prison industrial complex, The New Jim Crow, Vincent Harding's classic, There is a River, and Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon. Also: Asha Bandele’s The Prisoner’s Wife: A Memoir, the poems of Etheridge Knight, James Foreman’s Locking Up Our Own, and George Jackson’s Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson. Several faculty also mentioned the work of Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative as well as his TED Talk, “We Need to Talk about Injustice.“ For more information about the higher education in prisons initiative in the AYCGL, contact kipton.jensen@morehouse.edu or fred.knight@morehouse.edu.

______

Kipton E. Jensen is an associate professor of philosophy and the director of the Leadership Studies Program in the Andrew Young Center for Global Leadership at Morehouse College. His latest book is Howard Thurman: Philosophy, Civil Rights, and the Search for Common Ground (University of South Carolina Press, 2019).