The recent article in the New York Times Magazine by journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones titled “What Is Owed” is the latest in a long-standing black intellectual tradition that connects the history of slavery and Jim Crow to political claims in the present. In her essay, Jones overviews the generations of forced labor, violence, and exclusion that have had far-ranging consequences for black Americans and that continue to shape American life. America at its core, she argues, is defined by property, which provides the best measure of the country’s history of racial injustice. Because of the history and ongoing problem of systemic racism, white median household net worth stands at ten times that of the median black household, a gap that will likely grow without a concerted national response to the uneven impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent economic recession on black and white Americans. What to do about this and what is owed? Her answer is reparations now. Though an idea that a year ago was not embraced by the majority of Americans, the case for reparations has been around for centuries and probably will not simply go away. Like other social justice causes, the argument often long precedes broad acceptance.

A shortage of facts, reason or moral claims does not explain the inaction by the state on the question of reparations. Looking at moral revolutions such as the anti-slavery movement can be instructive in this regard. The anti-slavery argument and movement long preceded anti-slavery law. Africans resisted the slave trade at the point of origin, and black struggles for freedom continued in the Middle Passage and the Americas. The sixteenth-century French political philosopher Jean Bodin objected to slavery as a violation of natural law and a threat to state sovereignty. Led by the religious radical Benjamin Lay, Quakers developed their anti-slavery argument in the eighteenth century, an era when black anti-slavery writers including Olaudah Equiano, Phillis Wheatley, and Ottobah Cugoano also emerged. Only after generations of argument and struggle did they turn the tide. Women’s rights, labor, LGBTQIA+, environmental, anti-colonial, civil rights, and other social justice movements have followed similar trajectories.

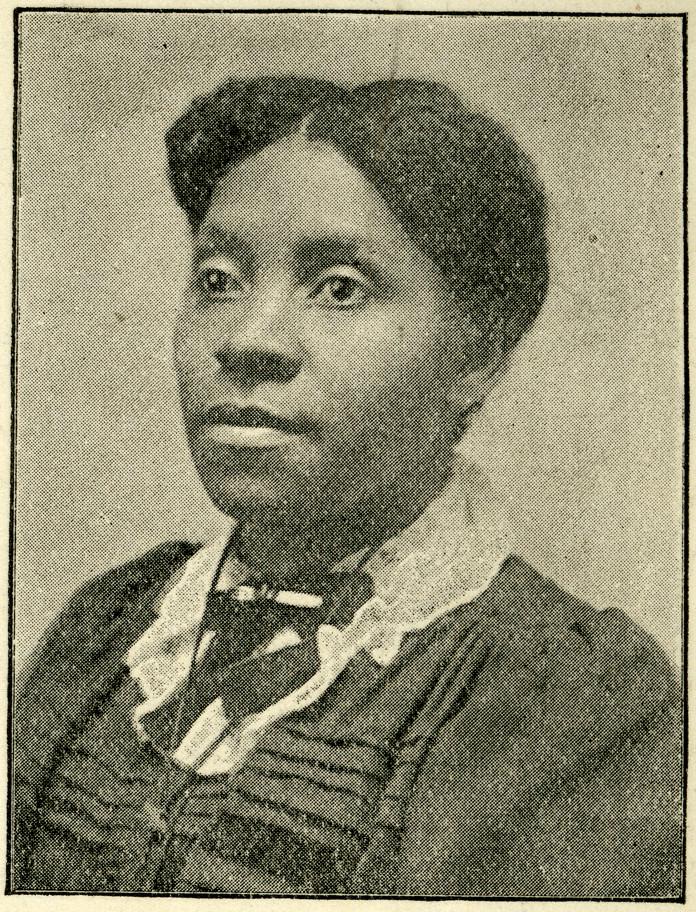

The argument for reparations has been part of black politics for centuries. In his essay “The Case for Reparations”, Ta-Nehisi Coates traces the idea of reparations to at least the late eighteenth century through the case of the former slave Belinda, who petitioned the state of Massachusetts for a pension to be paid from the estate of her former owner, who fled the United States during the Revolution and had his real estate confiscated. Then free but old and caring for her daughter, Belinda made her argument on the grounds that she had been denied “one morsel of that immense wealth” that her labor helped accumulate. Later generations would make the case. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman met with black leaders in Savannah, Georgia, about what they wanted. Led by elderly black Baptist minister Garrison Frazier, they asked for land to fully exercise their freedom. With his Field Order No. 15, Sherman set aside land and work animals, what became known as “40 acres and a mule,” for the use of freedmen and women on the Atlantic Coast, but his order was overturned by President Andrew Johnson. Callie House (pictured above), a former slave and domestic worker, organized a grassroots movement at the turn of the twentieth century to petition Congress for a law to grant pensions to the former slave population. She ultimately did time as a political prisoner in a federal penitentiary based on flimsy mail fraud charges. Others—Queen Mother Moore, James Forman, Randall Robinson, John Conyers—continued to make the case for reparations well into the twentieth century.

Given Martin Luther King Jr.’s wide-ranging and ultimately radical political vision, it is worth considering what he says on the matter of reparations. In Why We Can’t Wait, King couches his argument for historical redress in the context of a “Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged.” King writes, “The moral justification for special measures for Negroes is rooted in the robberies inherent in the institution of slavery,” a system that also scarred poor whites, who he argued should also be entitled to the Bill of Rights. By the end of his life, ending war, racism, and poverty stood at the core of his political work, which involved excavating and making material restitution for past injustice. His speech during the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign spoke directly about the historical roots of black poverty. During the Civil War, the Homestead Act divided up hundreds of millions of acres of land among its citizens, most of it going to whites. But in the wake of the War, the federal government failed to provide comparable entitlements to black freedmen and women as they made the transition out of slavery. This history, he argues, provided the basis for contemporary claims by black people on the state. More bluntly, he advised his co-workers in the movement, “When we come to Washington, in this campaign, we are coming to get our check.”

Over five decades later, black progress has been made but a deep chasm still divides black and white Americans. And as exhausting as it may be, the argument about what is owed will need to be made again, again and then again. Past generations did not know if, when or how their freedom dreams would be realized, but they continued to make the case until the powers that be conceded. Social justice workers kept pressing their claims for the sake of future generations, but it required more than sound intellectual arguments. There is no reason to think that the case for reparations will be any different.

______

Frederick Knight is associate professor of history at Morehouse College, where he is also director of the Institute for Research, Civic Engagement, and Policy at the Andrew Young Center for Global Leadership. Dr. Knight has published a number of book chapters and articles on black history, and he is the author of Working the Diaspora: The Impact of African Labor on the Anglo-American World, 1650-1850.

Tag(s):

Morehouse Faculty

Other posts you might be interested in

View All Posts

February 27, 2021 |

Morehouse Faculty