Back To Blog

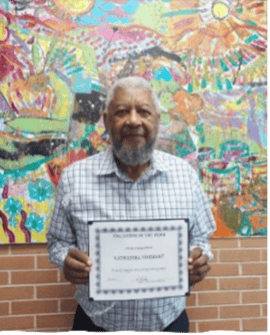

Morehouse Faculty, Professor Nathaniel Norment, Receives Volunteer of the Year at the US Federal Penitentiary: Writing Our Narratives.

October 6, 2023Written by: Kipton E. Jensen, PhD

Morehouse faculty member, Dr. Nathaniel Norment, who directs the Black Ink Project and Writing Center at Morehouse, recently received the ‘Volunteer of the Year Award’ from the US Federal Penitentiary [USFP]. Together with his colleagues, Professor Norment taught his signature class—one that he also teaches at Morehouse College—called “writing our personal narratives” at Metro Reentry (Spring, 2023) and the US Federal Penitentiary (Summer, 2023). As a teacher, Norment believes that the personal narratives written by the students inside Metro and the USFP “are not mere accounts of incarceration but reflections of lives transformed, lessons learned, and the indomitable human spirit. They reveal the profound impact of choices, circumstances, and society on individuals, urging us to confront the systemic issues perpetuating incarceration cycles.”

Teaching Creative Writing at the USFP in ATL

Students inside the USFP in Atlanta were immediately endeared to Dr. Norment as a person as well as a professor. Students inside appreciated his ‘overall approach to teaching,’' his entertaining stories’ and ‘winsome personality.’Quoting Orwell, Professor Norment believes that "[i]f people cannot write well, they cannot think well, and if they cannot think well, others will do their thinking for them." Morehouse is committed to developing men with disciplined minds who will lead lives of leadership and service. Beyond the democratic benefits of learning to write well, or at least better, Norment gives pride of place to Carter Woodson and Marcus Garvey. “When you control a man's thinking, you do not have to worry about his actions,” wrote Woodson in the Miseducation of the Negro, and Garvey is championed because he understood, profoundly, that “a people without the knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots.” As Director of the Black Ink Project at Morehouse, Dr. Norment emphasizes the importance of reading the classics of Black literature and writing about culturally relevant topics that engage the student where they are and contribute to what they want to learn as students at an HBCU. In a recent promotional video, Dr. Norment asserts that “[i]f you know who you are, where you came from, it empowers you.”

Professor Norment places his course objectives within a long tradition of Black men committed to telling their stories on their own terms: e.g., the narratives of Olaudah Equiano, Frederick Douglass, Langston Hughes, Malcolm X, Booker T. Washington, and Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as recent autobiographies from Ta-Nehisi Coates and Billy Porter. Each of these narratives demonstrates, writes Norment, “the extent to which Black men, since Middle Passage days, have been unadorned, unprotected, and undefended in a nation that has prospered only because of their strength, resolve, and unmatched genius.” Norment is quick to point out that his approach to teaching memoirs in prisons is not unlike how he teaches the signature class at Morehouse College: “The tradition of Black men telling our unique stories is what Morehouse College seeks to teach and continue in our quest for self-identity, self-affirmation, self-liberation, and self-determination.”

Curriculum and Classroom: Within Our Circle.

The basic curriculum includes selections from exemplary autobiographies (e.g., Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Frederick Douglass, and Wes Moore) as well as handouts chocked full of inspirational poetry (e.g., Dunbar’s I Wear the Mask and Nikki Giovanni’s Ego Trippin’ as well as Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and Walt Whitman’s Song to Myself) and aphorisms gleaned from various ethnic traditions (e.g., African proverbs and Latino adages or Haitian Creole sayings). Norment believes—because he has himself experienced it—that the practice of writing is cathartic or therapeutic. He is quick to quote his beloved Ralph Ellison: “If you know who you are, you can be free.” We write in the hope that we might understand ourselves and one another. It is often said that students will not care what the teacher knows until they know that the teacher cares for them. Perhaps more than anything else, the scholars inside Metro and the USFP knew that they were respected and cherished by the faculty as well as students from Morehouse who participated in the course and other AYC-HEP programming at these prisons.

The course itself is an admixture of retrospection and reflection about our personal narratives. Dr. Norment poses a wide array of introspective questions about self-identity, thirty of them, self-love, twice as many, since that’s sometimes the hardest part and the protracted problem, a series of ‘what if’ questions, thirty of those, self-forgiveness, which consists in a lengthy list of leading questions and a small set of therapeutic practices. Professor Norment asks each of his students to keep a journal, which he believes “can help us understand ourselves better—i.e., becoming more self-aware and mindful as well as resilient—while also improving mental health by reducing stress if not also diminishing depression or acute loneliness.” Writing can help us understand ourselves better, certainly, but it can also lead to a creative community of writers who come to understand each other, those of us within the circle of trust, both students and faculty alike, far better than before. Dr. Norment interweaves stories from his own narrative, which is compelling, into the formal curriculum.

Dr. Norment asks his students inside prisons, not unlike his students at Morehouse, to produce a 25-page ‘personal narrative’ over the course of an academic semester. According to Norment, the personal narratives composed by the incarcerated students are “a testament to the power of writing personal or reflective narratives as a tool for empowerment and healing.” Elaborating, Dr. Norment believes that these personal narratives are a balm to those who write them as well as those of us who read them:

"Within the confinement of their cells, these men have found solace in pen and paper, crafting narratives that transcend the physical limitations of their surroundings. In sharing their life stories, they reclaim their agency, refusing to be defined solely by their circumstances. Through their words, they invite us to see them not as prisoners but as individuals with dreams, regrets, aspirations, and the capacity for growth and transformation."

Excellent teachers like Dr. Norment understand that the scene of instruction changes from one institution to another, e.g., the students at Metro Reentry Prison and the students at the USFP, as well as from one classroom of students to the next one down the hall. The curriculum one selects is important, of course, but equally important is the commitment among the students behind bars to the value of the curriculum selected. Perhaps what matters most are the individual faculty members who deliver the curriculum and who build the trust with the incarcerated men and women we serve.

Congratulations, Dr. Norment!

Students inside USFP and those of us who work with him at Metro and the USFP, whole-heartedly agreed that Dr. Norment deserved this fine distinction as ‘Volunteer of the Year, 2023.’ It also demonstrates, they said, and we agree again, that this is what incarcerated men and women really want in terms of college-level educational programming. There’s no way to replicate Professor Norment, unfortunately, but we can nevertheless adopt as if to emulate the philosophy of education he personifies both inside and outside the gates of Morehouse College, as well as his creative approach to teaching and learning behind the walls of the USFP in Atlanta.

Tag(s):

Faculty Blog