Back To Blog

States of Justice: The Politics of the International Criminal Court

June 17, 2020Written by: Morehouse College

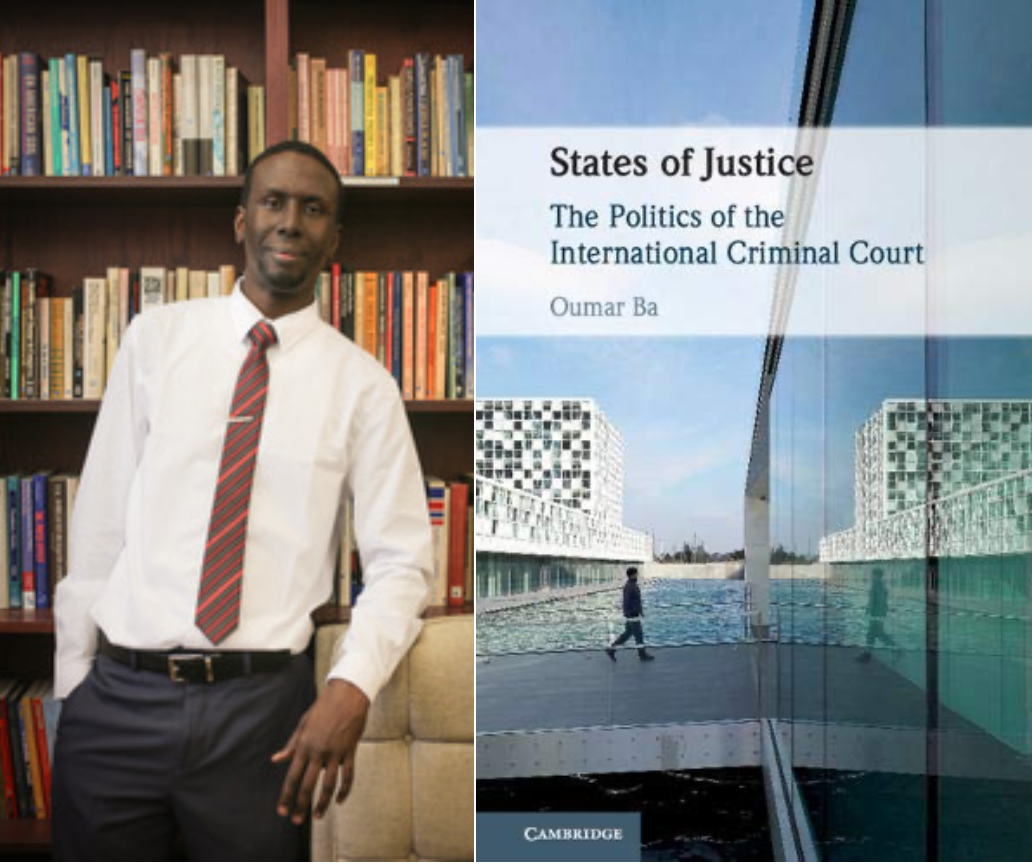

This post is part of the Faculty Research Committee's author interview series. Today the FRC shares a conversation with Dr. Oumar Ba about his new book, States of Justice: The Politics of the International Criminal Court (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

______

What key lessons do we learn from States of Justice?

In many ways, the International Criminal Court (ICC) was welcomed in euphoric terms and viewed as the epitome of an international legal order that would finally hold perpetrators of atrocity crimes – genocide, war crimes, and crimes of humanity – accountable, regardless of their nationality, rank, or who the victims were. My book dampens the euphoria of the “justice cascade” argument and the teleological discourse of progress which is advanced by the “road from Nuremberg to The Hague” narrative. I argue that the court has been utterly incapable of fulfilling its mandate mostly because we live in a world of states, and states have incentives and the ability to devise strategies to strategically constrain the court and actually use it in pursuit of their political and security interests, at the expense of “justice.” I focus mainly on how even states presumed to be weaker in the international system are able to use the court in such manner. So, in the end, the book does not offer really a hopeful vision for an international system in which justice is delivered in the name of humanity, even for committing atrocity crimes.

How has your research on the ICC impacted your teaching?

My research is grounded in fieldwork and critical perspectives on international relations (IR). Although I haven’t had much opportunity to teach courses that are directly related to my research, I still adopt that critical stance in the ways I teach my courses. Only my Intro to IR course fits what could be qualified as “mainstream IR.” In all my other courses, I’m unapologetically critical of the disciplinary approaches and I’m not interested in perpetuating the political science or IR canon.

What advice do you have for students interested in international law?

I would encourage all students interested in law (whether domestic or international), to think beyond law. I believe the emancipatory potential of law to be very limited. The rule of law is in fact at the heart of many oppressive systems. It’s important to always be reminded that slavery and colonialism were perfectly legal. The mass incarceration and current police brutality in this country is pretty much lawful. Why else would it be so difficult to charge and convict police officers for killing African Americans? How do the US government agencies get away with putting immigrant kids in concentration camps? So, in times like these, I think one must look beyond law, to seek and achieve justice. I believe justice is where one might find the passion and emancipatory potential to face oppression. And, yes, justice often demands breaking (unjust) laws – to paraphrase one famous Morehouse alum – and going after the “law abiding citizens” in order to dismantle the oppressive status quo. So again, I urge students to think beyond the law and the courtrooms.

What is your take on the Trump administration’s ongoing battle with the ICC?

The Trump administration’s stance regarding the ICC is probably only a slightly more grotesque continuation of the Clinton, Bush and Obama policies regarding the Court and international law in general. The US delegation at the 1998 Rome Conference where the ICC was founded tried very hard to make sure that the Court would be subjected to the supervision of UN Security Council. After many concessions made to the US demands, the Clinton administration finally signed the Rome Statute but never bothered to send it to Congress for ratification. Congress passed the “Hague Invasion Act” in 2002, which Bush signed into law. The Obama administration was less confrontational towards the Court, but only because the Court dragged its feet into moving forward with opening an investigation in Afghanistan, which would potentially put both the Taliban, Afghan forces, and US personnel under the Court’s jurisdiction. So, I would say the anti-ICC stance in the US enjoys a very strong bi-partisan support.

What is next for you?

I’m currently working on two book projects. One analyzes the current crisis of the international criminal justice system as a fundamental feature of the regime and asks what international justice would look like if we decentered The Hague. The second one continues my reflection on African states as makers, shapers, and contesters of the international order, looking specifically at the ways in which they used the UN General Assembly as a forum to assert their agenda for decolonization, both in a historical perspective but also in contemporary debates.

______

Oumar Ba is an assistant professor of political science at Morehouse and the author of States of Justice: The Politics of the International Criminal Court (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Tag(s):

Morehouse Faculty